Much earlier, I explored how the Merovingians viewed long, flowing locks as a symbol of status and sovereignty. Now, let’s take a look at an example from a different time, place, and extreme in the annals of mediaeval hair–the style known as the chahar zarb.

Chahar zarb is a Persian word translating as the ‘four shaves’, and was used to refer to the practice of shaving off the hair of one’s head, beard, moustaches, and eyebrows. It was a distinctive haircut associated with the group of Qalandar dervishes, but other dervish groups in mediaeval Turkey and Persia also practiced it.

Dervishes and Sufi mysticism have become an increasingly popular topic, especially as the poems of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi become more available in many languages. The Qalandar dervishes, however, took ideals of mystical pursuit of God to extremes, eschewing wealth, a steady career, a permanent home, and a place in society. To them, it wasn’t enough to leave society and live like a hermit. Instead, Qalandars chose to demonstrate their lack of attachment to this world by violating taboos and visibly breaking with community norms.

The chahar zarb contributed to these activities, but to understand how we have to take a look at what Abu Talib al-Makki, a Sufi and Islamic jurist, had to say on the subject of beards.

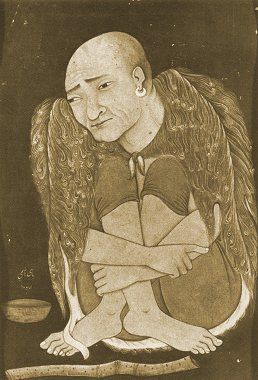

This 15th century Timurid depiction of a dervish shows him beardless with a shaved head and moustaches, but eyebrows seemingly intact (Source.)

For him, beards distinguished men from women, writing “ the beard serves to perfect the natural characteristics of the man.” (al-Makki, p.100.) It was also a way for a pious Muslim to emulate the Prophet Muhammad in his daily life, since both the Prophet and many of his most distinguished companions wore beards. In a treatise on the subject, he explored the traditions relating to the Prophet’s beard, giving instructions as to how it should be trimmed, what length it should be kept, and other details.

Beards weren’t all good, however. Because they signaled status, learning, and dignity to others, they could be a source of vanity and pride for their owners. He cautioned against dyeing the beard to appear old and wise, to put on false youth, or dyeing it a reddish or yellow colour unless a sincere imitation of Qur’anic personages was intended, (al-Makki, p.101.)

He makes another remark too, which helps us to put the Qalandar dervish attitude towards hair in context. According to him, some men chose to wear their beards long and disheveled in order to display their asceticism and piety to others.

For the Qalandars, then, shaving in the chahar zarb style allowed them to reject social norms and even well-recognized symbols of piety. Historian Lloyd Ridgeon also suggests that it symbolized their spiritual rebirth. Alternatively (or perhaps simultaneously), it contributed to their self-identity as those who had embraced a social death before a spiritual one.

These meanings were intricately layered and communicated within dervish groups, but it’s unclear how many non-dervishes would have understood these interpretations. Mostly, however, they would not have had too. These four unusual shaves, combined with the animal pelts, metal adornments, and anti-social behaviour which also characterized Qalandars were a visible sign of their spiritual path that very few would have been able to misinterpret.

Further Reading:

Karamustafa, Ahmet T., God’s Unruly Friends: Dervish Groups in the Islamic Later Middle Period, (Salt Lake City, 1994).

Ridgeon, Lloyd, ‘Shaggy or Shaved? The Symbolism of Hair among Persian Qalandar Sufis’, Iran and the Caucasus 14 (2010), pp.233-264.

Abu Talib al-Makki, ‘The Beard’ trans Douglas, Elmer H. , Muslim World 68 2 (1978), pp.100-110.